Manufacturing Readiness Grants (MRG) provided by the Indiana Economic Development Corporation and administered by Conexus Indiana are available to incentivize, de-risk and accelerate the adoption of innovative manufacturing technology for small- to mid-sized manufacturers in Indiana. An MRG of $200,000 helped enable critical pieces of Tactile Engineering’s automated production line, expanding capacity and increasing the company’s workforce.

Tactile Engineering

Case Study

Key Stats

Company History

Three Lafayette entrepreneurs founded Tactile Engineering in 2013.

Friends and colleagues Dave Schleppenbach, Tom Baker, and Alex Moon founded Tactile Engineering (Tactile) in 2013, and were later joined by their friend Wunji Lau. Their shared mission: to lower communication barriers for people with disabilities — primarily blindness and visual impairment.

“The key here is Dave,” said Wunji. “He graduated from Purdue wanting to solve the problem blind students have in both enrolling and succeeding in higher education. It’s difficult for blind students to get adequate math and science education needed for the careers they want. Assistive technology is a niche industry, with lots of high-tech processors used in ways mainstream industries don’t often use them. And the products that do exist tend to be very expensive. Dave wanted to solve the blindness education gap that was a very personal part of his life,” Wunji explained.

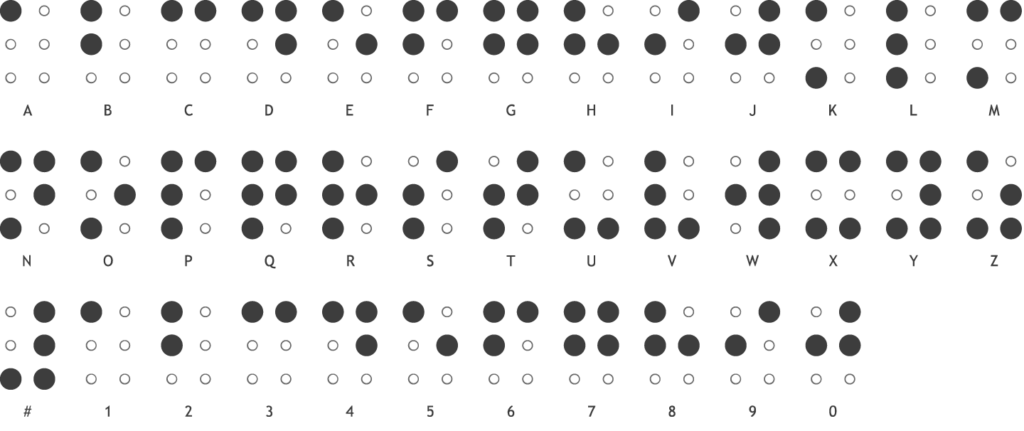

Dave’s wife Wendy was blind. The two were married young and, by the time he went to Purdue, Dave had already learned braille and much about accessibility — including that there are many different braille codes. A braille cell is comprised of a 2-by-3 matrix of 6 dots and typically represents a single character. Depending on the code used, a cell can represent a letter, number, punctuation mark, or even a musical note or math function.

Source: Pharmabraille.com

Proficiency in braille math code is far less common, especially among sighted people, than in braille English code. When Dave learned that visually impaired Purdue Pre-Med students were having difficulty using English braille code for math and science tasks, and was asked if he could help, he built an accessibility services lab to provide class materials in braille math code and develop accessible teaching tools for chemistry and biology subjects. “The whole time Dave was working with those students,” Wunji said, “he was writing and creating materials for the students and for his wife, as well. The more professionals those students worked with, the more blind PhD chemists, engineers and other professionals they met, the more they said, ‘I want to have a job in aerospace, in space science.’”

Using knowledge and experience from their early tech ventures, Tom and Alex had “a great idea on how to accomplish our mission to lower communication barriers for people with disabilities — primarily blindness and visual impairment,” said Wunji. Tactile Engineering was built around this idea: to exceed the limits of existing electronic braille devices and create a portable device that could show not only braille but also tactile graphics and animation, a decades-old technological dilemma that the blind community had come to refer to as “The Holy Braille.”

Initially, Tactile struggled to develop an effective, low-cost advancement to existing assistive technology for blind and visually challenged individuals.

Prior to Tactile Engineering, a few patents and prototypes existed for this technology, but even those from Purdue, MIT and the US Air Force had not succeeded in making a practical device. Part of the problem was that the device’s niche market made it prohibitively expensive to manufacture at a small scale. Some attempts focused on developing new kinds of braille and tactile graphics. Others worked on mobile apps. “But the dream was always to make a tactile computer screen — those never quite worked,” Wunji said. “The problem is far more difficult than most think. Over the decades, many have tried, and all have had trouble. A lot of devices are designed by people who have a desire to make something that can help people, but they can’t make it a viable product. Their prototype might be beautiful and 3-dimensional, but there’s no way you can mass-produce it. It’s a functional one-off idea.”

Tactile’s business plan focused first on the mass-producibility of a tactile device. After developing 5-6 prototypes, Tactile earned its first big customer with a local connection at the Indiana School for the Blind. “When we told them we were starting production for the Cadence Tablet and ready to get going, they were the first ones to sign on,” Wunji recalled. “We made our first big delivery to them.” Since then, the school has been enormously helpful, he added. They use the device, test it, put it through its paces and report when something needs to be fixed or improved. “It’s great when people are honest with us, when they say, ‘hey, fix this’ rather than just decide they don’t like it and disregard us.”

Similarly, Tactile built on existing relationships in Indiana from the founders’ days at Purdue and through the years since. “From getting our initial production robots for the facility to our first injection molding, we used Indiana companies we had either known back in our Purdue days or from our own experience to keep manufacturing close by and localized,” he said.

The Project

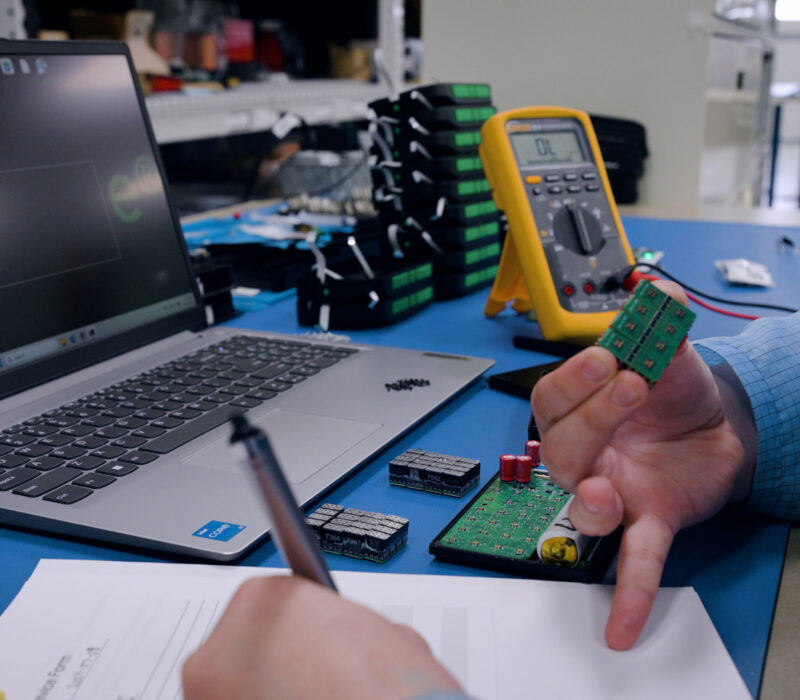

Each Cadence tablet requires 25,000 parts, and assembling each part is intensely involved — not an ideal task for human work, but a fitting challenge for Conexus Indiana Rising 30 honoree Nick Will.

In early 2023, Tactile received a $200,000 MRG grant to expand and improve its then-operational production line for the braille modules in its Cadence tablet, and to build networked automation for their assembly. To expand manufacturing capacity, Tactile would duplicate existing automated robotic equipment and inspection systems; new cobots and IoT-linked systems would also be integrated to test the Cadence devices. The plan was to add new hires to augment Tactile’s engineering and technical staff — assisting with the development, implementation and maintenance of new equipment and software within Tactile’s Lafayette facility. Conveniently, Nick was looking for full-time employment in a hands-on product development role, and began working at Tactile as a Purdue senior.

Throughout the expansion, there were problems seeking solutions, and Nick was the mastermind at finding those creative and innovative solutions. “I started at Tactile primarily doing a lot of the production tech stuff, which was useful in making me familiar with the process,” he recalled. “Then, given my engineering background, I transitioned to more of the engineering application.” The precision required to build the Cadence Tablet is nowhere more evident than in the placement of the “dots” that are electrically actuated to create readable braille characters and moving images. Nick was able to solve one of Tactile’s largest assembly bottlenecks by designing, programming and building an elegant manufacturing solution for these dots.

“The top enclosure of our tablet houses 12 modules, with 32 holes each, for a total of 384 holes. The modules have plungers — think of them as a disk with a rod in the center that travels up and down,” Nick explained. Those individual plungers form the bases of the rounded dots the user feels on the surface of the screen. Initially, an operator sat for 30 to 45 minutes with a pair of tweezers, taking one dot and dropping it into a hole, then taking a second dot and dropping it into a hole, and so on for every device. Wunji shared his own story about the difficult process. “No one wanted to do that job. One night I had to do it for our initial prototype. We worked through the night and were hundreds of dots in when we dropped the tray. We cried. And started over.” Robots to replace the operators were suggested, along with other solutions. But the cost and the programming for such a unique application eliminated the option of farming the task out. That’s when Nick went to work on the solution.

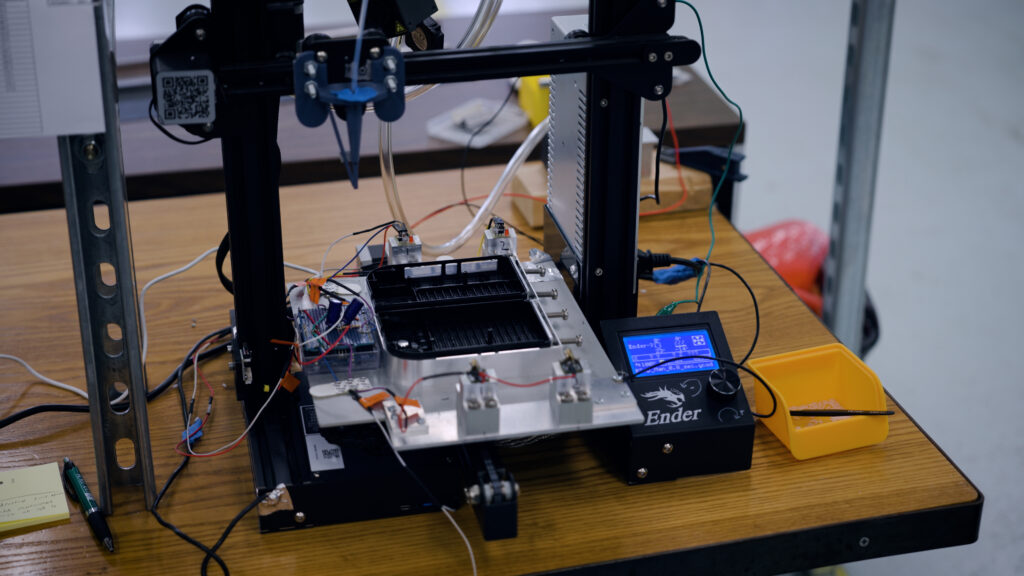

Nick created the “Dot Bot” to automate precision dot placement.

The specifics of the “Dot Bot” are best described in Nick’s words:

“I took an on-the-market 3D printer and used it as a series of linear actuators,” he said. Despite their vastly different uses, a 3D printer served as an excellent mechanical and digital foundation for automated dot placement. “I took off the printer nozzle, took off the wheel and the heating element, and wired the heating element to a vacuum pump. That controls the robot to tell it to turn on the heater, and it turns on a vacuum pump instead. The vacuum holds dots in position until they need to be dispensed, and that is triggered by a series of laser receivers being broken.”

“I designed a 3D-printed fixture to dispense the dots, and we got a bowl feeder that integrates with that. I also wrote a Python script that takes dot installation coordinates and translates them into code that the robot can understand and position itself with. The Python script will take those coordinates and move the robot between the locations.”

The programming required for Dot Bot’s task is more sophisticated than you may think. “It doesn’t just go to the first dot install location and move on to the next and the next and so on – because it’s a 3D printer with limited accuracy and tolerance, the script makes it go to a location and form a spiral around the dot install location while releasing vacuum and installing the dot. So, if there’s a little bit of deviation of where it’s supposed to go, the dot can automatically center itself, find its home, and drop in.”

“People may ask, ‘why don’t you just make the dots or the holes that contain these coils a little farther apart or the block a little bigger?’ We can’t do that, and refuse to do it, because the spacing of the dots is identical to printed braille the users now know. Someone who already knows braille or uses it can easily transition to using our device as opposed to having to relearn it because the spacing is different. That’s why we have such tight design tolerances and won’t compromise and change the tablet’s format; we want its output to be the same as printed media so blind and visually impaired users can easily transition between the two.”

“We had to find a ‘Nick,’” Wunji said. “A Nick who wanted to do this type of thing and wanted to work in a mission-driven organization. It was a super-technical challenge to solve and that’s what it took. We’re very lucky to have Nick who was exactly what we needed and is as passionate about this project as we are.”

Key Learnings

To know where you need to improve, it’s necessary to know what you need to improve.

One learning Nick was willing to share: It’s best to first understand what you need to improve before experimenting. “It was easy to think I needed to start innovating immediately,” he said. “My first few months working as a production tech – making the parts, running the robots and assembling the models was valuable for me before filling an engineering role.” When engineering solutions required close communication with production, Nick could understand what his production team was saying because he had done that job.

Wunji agreed and went on to say that solving one problem often reveals several other problems you didn’t know existed. “For anyone in a startup, especially a tech start-up, you must be able to maintain your focus and your sense of morale as that happens. Be prepared for it and go into it understanding that you will solve this problem. And tomorrow you’ll come in and you’ll see 5 more problems developed from that solution. Be ready for it and be ready to power through it.”

Wunji also recommends prioritizing financial aptitude. “Our CFO is amazing,” he said, “and that leads to grant opportunities working with state agencies and agencies like Conexus Indiana for MRG grants, working with Purdue for the Manufacturing Extension Partnership grants. We wouldn’t have the production line we have now if we hadn’t worked with Conexus. We wouldn’t have the trained crew we have now if we hadn’t worked with Purdue. These are the kinds of resources you must learn exist and learn how to use. Our engineering is vital, of course, but there are several parts that must come together and function in sync for a company like this to succeed. A good CFO is absolutely vital to this company,” he counselled.

Workforce Implications

A multi-disciplinary workforce is an indispensable asset in a start-up organization, and a relationship with good educators can help fill those needs during growth periods.

“Honestly, being located in Lafayette near Purdue has been great,” Wunji said, noting that Purdue has a wealth of well-educated, trained engineers and has provided many that contribute to Tactile’s success. Finding employees with the right kinds of skills, personalities and business minds to make that product marketable isn’t always simple, he explained. “In technology, you can build companies by having a couple of people with those skills. But if you miss any key strength areas like business, technology/engineering or accessibility, you’re not going to be able to make the margins and the volumes needed for success,” Wunji guided. “Margins get tight, and volume gets too low. You must be on target and on target early.”

A multi-disciplinary workforce can cut through the confusion that sometimes plagues start-ups. “Start-up environments tend to be messy,” Wunji added. “They are fraught with risk. But the big advantage is they’re also agile, adaptive and, honestly, they’re fun.” The flexibility of a workforce where everyone wears multiple hats and is trained in different disciplines can work well. Tactile’s 4 founders met that requirement, and they prioritized assembling a workforce that shared the sense of adventure and problem-solving needed for success in a start-up environment.

But, he cautioned, intuitiveness and passion are not enough to create success. “As we grew, we needed production floor managers, a software department and software developers, a hardtech technology department, and someone with broad oversight over the entire facility — a COO,” he said. “All of that is what’s required to be revenue positive and profit positive.”

Project Success

The success of Tactile’s MRG project is seen in its ability to introduce the Cadence device to more who need it at a price they can afford.

“Compared with our situation before the project, we’ve grown to about where we wanted to be at this time,” Wunji said. “We knew we needed to be producing hundreds of these to fill our space, meet the orders to at least our surrounding states.” Of course, every company would like to see its markets expand faster and grow. “But,” he shared, “it’s better that we continue to iterate at this level while we’re here, continuing to refine and improve. So, when we do take that next big step to scale, we have everything worked out as much as possible.”

Still, he said, scaling is a worldwide problem. There are several other countries with a similar growing demand for the Cadence Tablet. “France needs 10s-of-thousands of these devices. We’re hoping to duplicate this line and continue to develop and expand into the worldwide market. The more that are out there, the more powerful it is.”

He envisions a future where there are blind people across the world communicating with each other in real time with Tactile’s Cadence tablet, sending tactile messages to each other, drawing collaborative graphics in real time. “That’s the community that we’re building,” Wunji said. “The power of that community is growing exponentially as we add more people.”