Manufacturing Readiness Grant Spurs Growth for Complexus Medical and Opportunities for its Workforce

Company History

In 1990, David Behrens purchased F&F Machine Specialties, a small machine shop in Mishawaka, Indiana, and the family business has evolved into the manufacturer of complex medical components and orthopedic instruments it is today. Noting the company’s proximity to Warsaw, Indiana – known as the orthopedic capital of the world – the owners set out to diversify into a supplier of components and assemblies for the medical market. Today, under the leadership of David’s son Michael as President, BBS Enterprises dba Complexus Medical (Complexus) delivers high quality orthopedic and spine instruments. Its reputation is built on ensuring each device meets statutory and regulatory compliance. In 2020, the company purchased a second location in nearby Plymouth to supplement the production capabilities of its Mishawaka plant. Plymouth has become home to Complexus’s advanced manufacturing plant, while the company’s headquarters remain in Mishawaka.

“In the orthopedic industry, you have instruments and implants, and we are 100% instruments,” Michael said. “Within that space, we focus on the more difficult or complex, hence the name Complexus Medical. We do the multi-piece welded finished assemblies, the stuff that other people don’t want to do. That has reduced our competition worldwide, created a niche for us and protected us from some other, lower-cost countries. OEMs in the medical device space do not like to outsource if they can get a competitive price in the U.S.” With that competitive price, Complexus today boasts 127 employees — a 21% increase over the past year — and is growing its sales. “I can grow my revenue faster than I can grow my workforce,” Michael stressed.

The Project

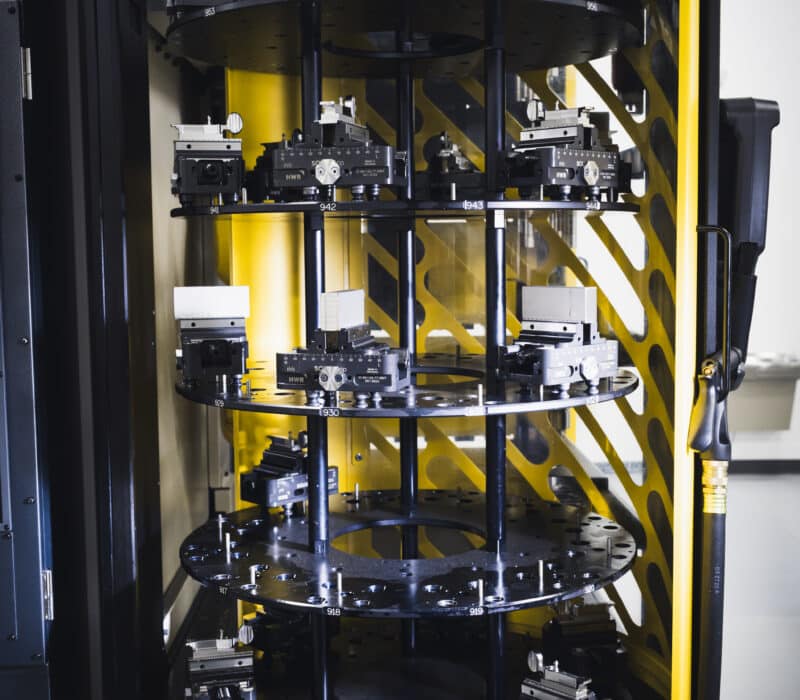

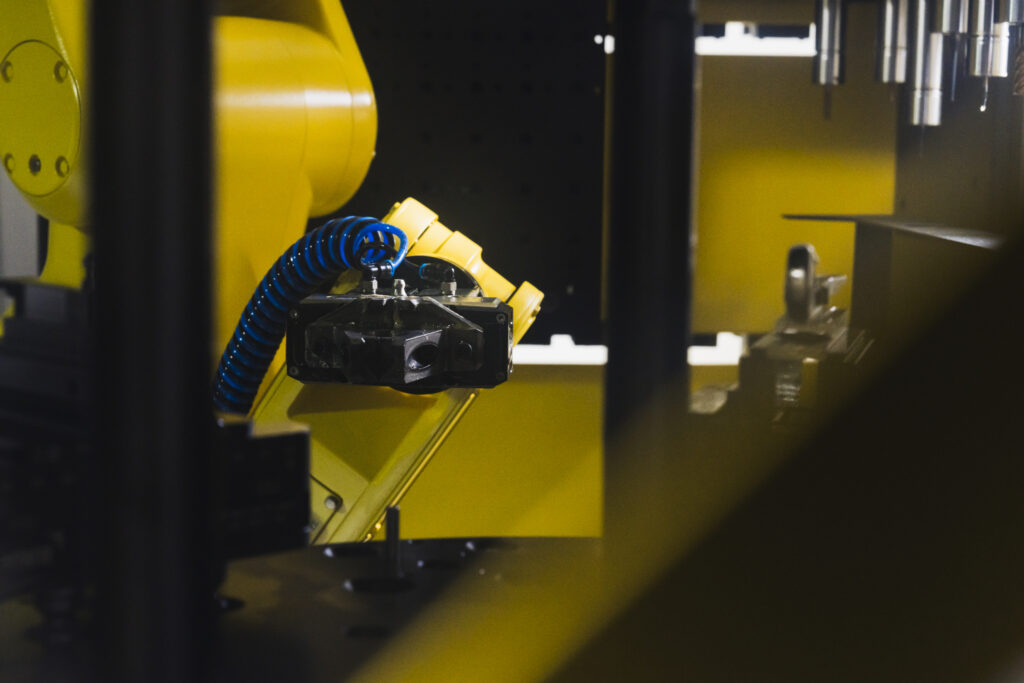

The $200,000 grant awarded to Complexus supplemented the purchase of a robotic machining center – comprised of a 6-axis articulating arm with milling, drilling and tapping capabilities, rotary workpiece storage carousel and digitized tool management. “Once we established a successful workflow with that MRG-enabled equipment, we were able to acquire a second machine on our own and increase capacity,” Michael explained. “Automating production of one part is not easy,” he said, “but it’s a one-time thing. For our lower-volume, higher-mix product line, automation needs to be method-focused and not part-focused. How do you make an automated process that works for parts that don’t fit into the first line? You make a CNC program.” Once established and vetted, that program and automated system increases manufacturing flexibility and efficiency. As Michael described, “Let’s say the cycle time was 30 minutes on a standalone, non-automated CNC. If it runs on the automated machine, its cycle time is 34 minutes. But, if I’m running it with no operator standing in front of it over time, those four minutes are nothing.”

Complexus chose Meredith Machinery as its preferred vendor for the machining center because of its representation of top equipment brands and its service reputation. “If you want a CNC mill, there are five or six brands that are plus or minus nothing of each other. They can all do the right job, so it comes down to service. The best machine in the world doesn’t mean anything when it’s down,” Michael explained. “Meredith provides the highest level and quickest service for us, and their machines have the lowest downtime.” Meredith’s automation support also eliminated the need for Complexus to bring in other companies to supplement the installation and training.

Manufacturing Readiness Grants (MRG) provided by the Indiana Economic Development Corporation and administered by Conexus Indiana are available to Indiana manufacturers willing to make capital investments to integrate smart technologies and processes that improve capacity. A $200,000 MRG awarded to Complexus Medical supported the installation of the company’s first automation line and is the basis for a continuing smart technology renovation.

Workforce Implications

Instead of furloughing workers because of automation, Complexus has increased its workforce by 21% year-over-year since it adopted the equipment that allows for lights-out operation without adding shifts. That makes finding employees willing and able to work overnight and weekend shifts no longer an issue. “It’s this equipment that actually makes that possible,” he added. “Five or 10 years ago, there was automation and robot-fed machines, but you had to buy all the pieces separately. Now they talk to each other. This one uses smart technology where the robot is part of the CNC. There is one control screen, and it was integrated before it was installed on our floor.”

Michael is a proponent of education. College-educated himself, he appreciates its value but also recognizes the value of all educational paths. “I have employees here making six figures,” he said. “It was all on-the-job training. Ivy Tech does a really good job. We have several of their graduates. You find someone who wants to work, will come to work, is willing to show up every day on time and put the effort in. Someone who is inquisitive and will lean in and learn. They’ll ask the right questions and absorb the information. It’s a mix of education and attitude and the job skills and opportunities.”

Opportunities for employment advancement abound at Complexus, he added, where the engineering department currently has nine engineers. – Of those nine, less than 20% of them have a 4-year degree. Complexus has also awarded machinist role promotions to former delivery van drivers and receiving clerks. “For every entry-level job you lose, you promote to an engineer or technician with increased wages.” At Complexus, employees earning that increased pay are typically existing workers growing in knowledge and ability, and college completion is not a prerequisite. He pointed to a machinist who came from a nearby plant that stifled his ambitions because he lacked a 4-year college degree. “No one would give him a shot without that college background,” Michael said. “He came to us as a machinist and 18 months later is earning a significantly higher salary.”

Shared Learnings

“The salesman is always going to tell you it’s going to take half as long as it does,” Michael advised. “You should just double that, keeping in mind that twice as long is at least twice as expensive.” When something is expected to take four months, remember that it may require more to get the equipment in place and working. Take all the time needed to make certain not only that the equipment is working, but that it’s performing at its best without supervision. “Not when there’s someone standing in the building, not when there’s a manufacturing engineer around, but when the lights are off,” he said. “It’s no joke. The lights really are off. There’s no one there, and there’s just the light of that machine.”

Speaking more broadly on the future of manufacturing, Michael captured: “What I’m worried about are the small manufacturers that would attend a seminar or webinar and see examples of these super automated things – these small manufacturers would say ‘that’s interesting, but that’s not me – how could I ever make that work for my business?’ But you’ll see it implemented in the future and then it’s like ‘I don’t know that I’ll be buying anything that’s not automated anymore.’”

“I have to have it first – and that’s what the MRG program has helped us do – put this equipment on our floor.”

Michael Behrens

President of Complexus Medical