DuraMark Technologies Invested a $150,000 Manufacturing Readiness Grant in Label Production Technology to Reduce Manual Steps and Increase Production Capabilities

Company History

Today, DuraMark serves the automotive, construction equipment, ag equipment and other industrial equipment industries that require labels to remain on their product for their entire lifespans. The plan, Bill said, was to “disrupt the traditional label and decal printing industry by allowing manufacturing clients to take control of the labeling of their products.” Initially, the idea was to develop equipment that made it possible for manufacturers to create and produce their labels on-site at their own plants. It became clear, though, that manufacturers preferred to purchase their custom labels from professionals in the label industry. So DuraMark pivoted and focused on working with manufacturers to design and create labels at its own plant, where it prints custom labels and delivers them to its customers.

Today, Bill remains CEO of DuraMark, and the company is one of the fastest growing in the digital printing industry. Headquartered in Westfield, Indiana, it occupies a market niche delivering durable decals fast, focusing on protecting people, promoting customer brands and providing opportunities for its employees. That success was built on the original label manufacturing equipment DuraMark engineered and built in-house.

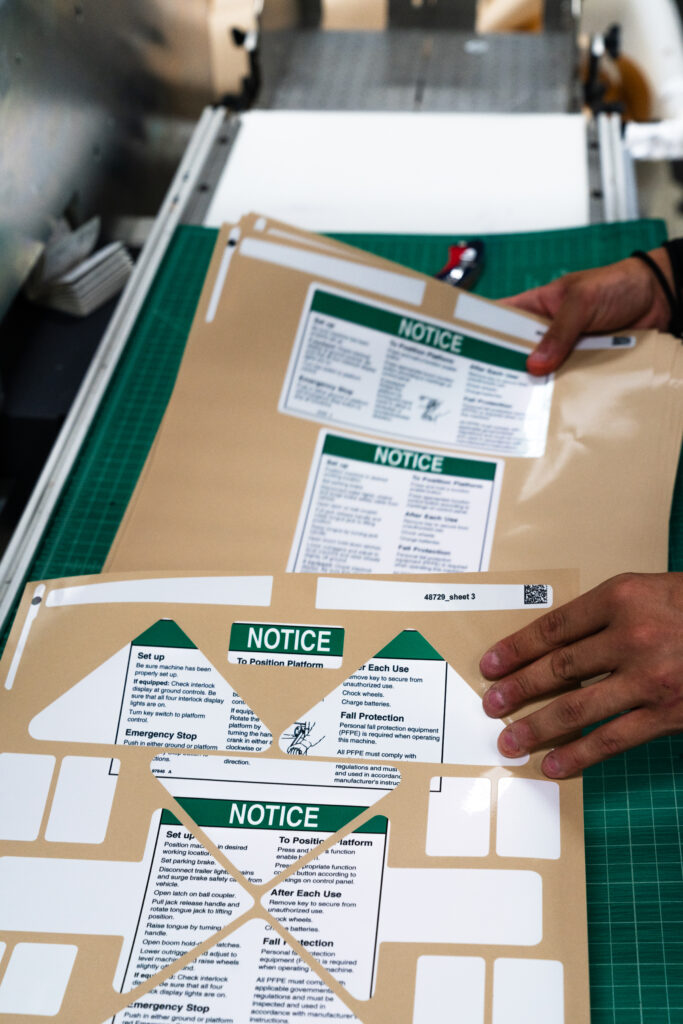

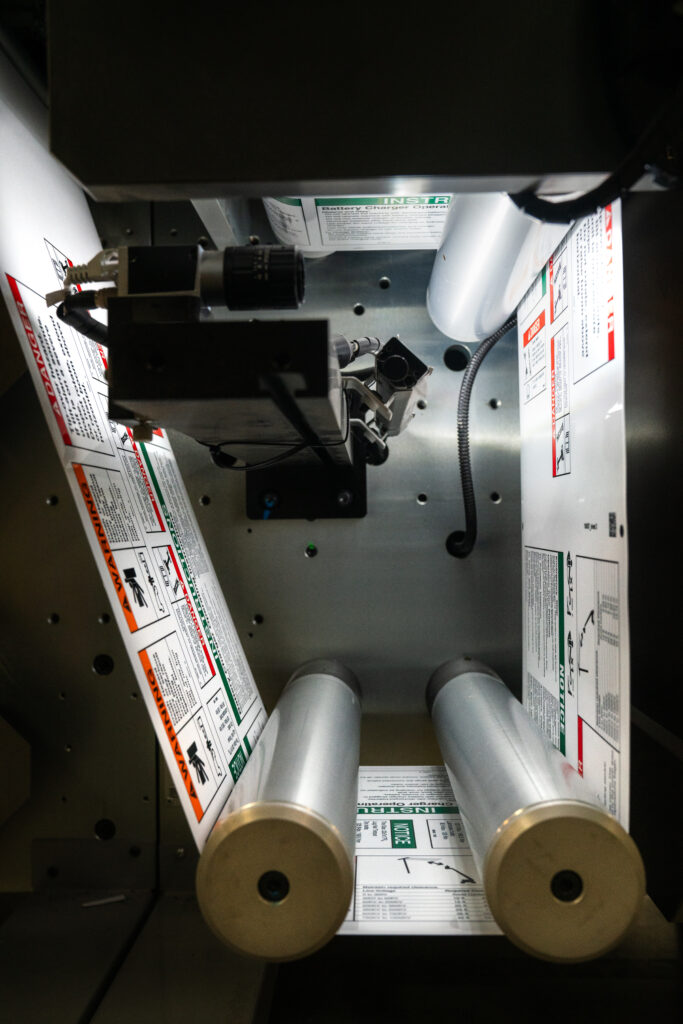

Labels are first printed on a base substrate material such as polycarbonate, polyester or vinyl. Once printed, the label conversion process involves specialized machines, often referred to as converters, which apply coatings such as UV protections on labels and then cut individual labels to size. “We produce labels for the industrial manufacturing market,” said Stacy Hiquet, Vice President of Talent Acquisition and Training. “Our labels are weatherproof, fade proof and can last longer than traditional labels.” Common types include safety, instructional and branding labels – all manufactured with longevity in mind. “When you see a piece of machinery, you’ll notice it can have anywhere from 20 to maybe 200 labels,” Stacy explained. “We do all those labels for our clients.”

The Project

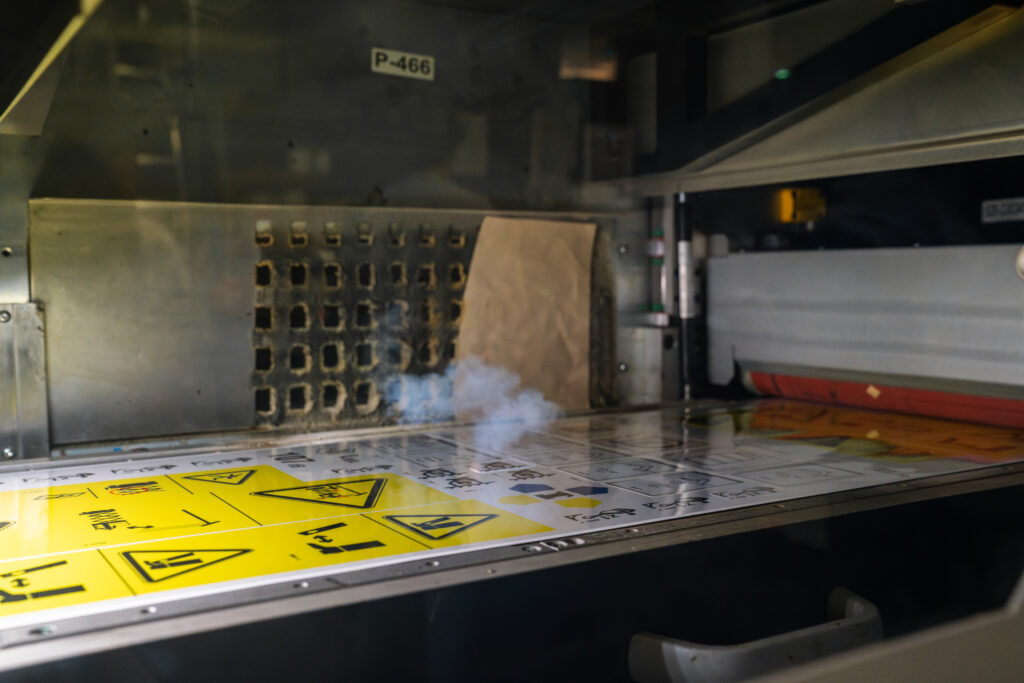

Using the original purpose-built converters, printed labels were fed into the converter where they were laminated and cut to the designed size and shape to complete the order. That was the baseline from which the project evolved. “When we applied for the grant, we were talking about new technologies that could change our business,” said Stacy. Those technologies would operate at greater speed and with a precision that far surpassed what was available on the earlier converter versions. She described that precision using her name — “Stacy” — as an example. If removing the center of the “a” was necessary to execute the label’s design, the older converter required an additional processing step; after each label was printed, it was removed from the converter for ‘centerpieces’ to be manually detached, adding a tedious and time-consuming step to production. The new technology in DuraMark’s acquired label converters automates the removal of these ‘centerpieces’, improving production time and freeing employees to perform more skilled tasks.

Jeff Prichard, Vice President of Operations estimated the time involved in that single, seemingly small improvement. “We estimate that automating this step saves a half-second per removal, and there might be 200 of those with each ‘pick’ or run of a single order unit. If 30,000 of those picks are pulled out over a 3-week period, the automation is saving us 75,000 seconds, or about 21 hours.”

Efficiency gains are also quantified with the elimination of a dedicated pre-masker machine, which is used to apply the pre-mask after the material was already converted. “We used to spend 3 to 4 hours a day running the pre-masker machine,” Jeff said. “I estimate we cut down that time by some 25% by running the pre-mask directly on the machine where it is now automated.”

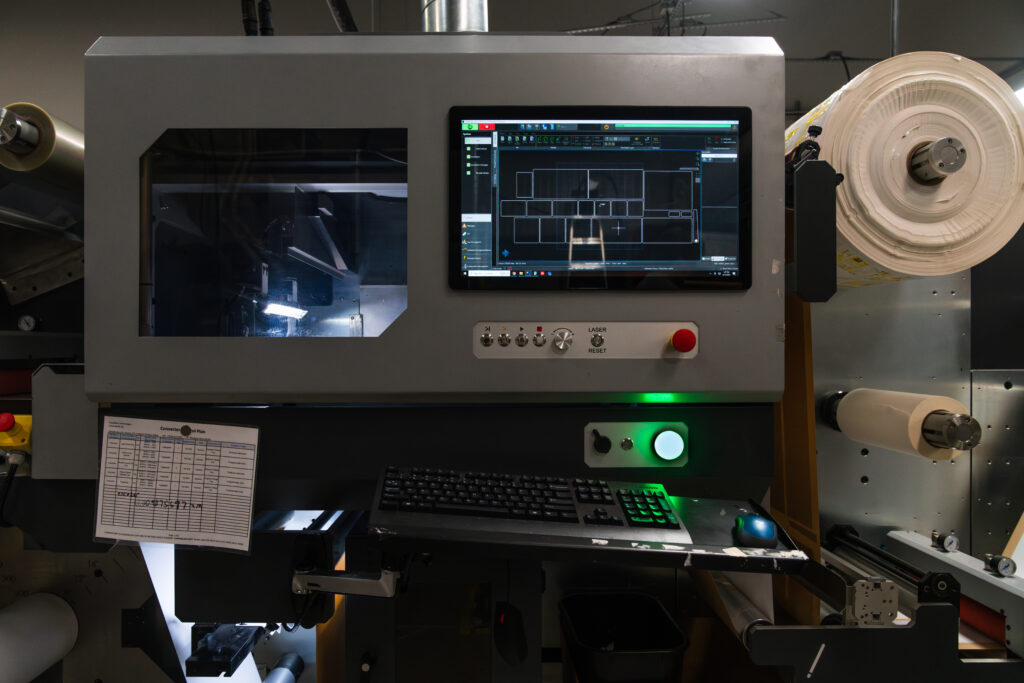

The technology incorporated in the new converter enables automated process adjustments, like increasing or decreasing production speeds. “We get the optimal run time on the machine and have fewer mistakes because it’s automatic… we are able to pre-program the converter for each individual run,” Jeff explained. “It’s not dependent upon an operator entering the parameters onto a screen. Before this new technology, we had lots of manual tasks and a lot of adjustments that needed to be made.”

Now, the operator isn’t sitting in front of the machine twisting knobs, frequently leaning left or right, punching numbers into a screen. Their involvement is still critical to successful label production, but human operations involve fewer safety and ergonomic challenges. An operator is now stationed at the end of the machine – a safe distance from potential equipment hazards like the laser cutter – and is either stacking finished labels or prepping labels for the next step in production.

The new converters have also allowed DuraMark to enter a new label market and diversify their offerings by producing labels on rolls, in addition to fanfold, accordion-style labels or flat stock.

Manufacturing Readiness Grants (MRG) provided by the Indiana Economic Development Corporation and administered by Conexus Indiana are available to Indiana manufacturers willing to make capital investments to integrate smart technologies and processes that improve capacity. DuraMark Technologies’ $150,000 grant enabled significant upgrades for its label manufacturing process.

Workforce Implications

Not everyone embraced the new technology at the beginning of the project. “We had one machine operator who found the technology a little too advanced,” Stacy recalled. “He really liked to work on the old converter, and he never did adapt. When a previous employer offered to reinstate him, he elected to return there rather than to qualify on the new DuraMark equipment.” Everyone else did become qualified, and DuraMark’s current group leader has been effectively cross-training employees for improved operations coverage and to offer more career growth paths.

Their hiring process now includes a technical evaluation to validate an operator’s ability to comfortably work with tech-enabled equipment like this converter. “Because of the new technology, we now do a very basic computer test to ensure they have at least minimal computer skills and comfort,” Stacy said, citing some minor Excel work and email abilities. “We need to see some level of computer comfort so an employee will be able to grow and do all the cross-training.” Successful production requires available and qualified employees to step in and fill a position when there are scheduling challenges, she said, adding “We want more people to know the different aspects of the plant floor and the different machines, so people can grow from within.”

Shared Learnings

DuraMark’s engineering team was tasked with recommending partners on the project, settling on Grafotronic, an international firm in Lake Zurich, Illinois, to build the machine – largely because of its quality industry reputation. LasX, another international firm with offices in St. Paul, Minnesota, was chosen to provide the laser unit for cutting.

The training program provided by the partners was very good, Stacy acknowledged. One operator went to the Grafotronic plant in Chicago for the acceptance testing and pronounced himself very impressed. He said he wasn’t just watching the equipment run; he was able to participate in the process, ask questions and learn how to respond to specific issues. “That was one lesson confirmed for us,” Stacy recalled. “We needed to have someone who was either from the printing industry and really understood converters or who had a very significant engineering background involved in acceptance testing.”

In addition, DuraMark found that writing its own custom-tailored manual for converter operations to be a requirement for work on the manufacturing floor. The realization was had that vendor trainers are experts with the equipment they’re installing, but DuraMark would need to supplement their provided documentation with their plant’s existing processes and requirements to capture the entire operational picture and ensure success. “We started writing our own user manual – it really was a necessity,” Jeff said. “The training itself was a good experience, as was the follow up. After the fact, they would send their tech down and help us with any problems. All in all, it was a pretty good experience.”

He and Stacy agreed that sensitivity to existing plant culture and having a designated project champion on the floor alleviates many of the snags that can arise when new technology is introduced to an established environment. For example, including existing company subject matter experts in organization-wide communications provides a smoother introduction to new technology for all – especially when it comes to job creation and growth. “When I talked about our label converter cells, I was careful to explain that, yes, the new technology will possibly take a 5-person cell and reduce it to a 2-person cell. But we’re growing and we’re not going to let people go,” Jeff said. Stacy added, “You have to do a great job recognizing that culture. A lot of these folks may hear ‘automation’ and they think their jobs are going to be gone. You need to watch how you’re saying things, and how the automation is going to come in. We addressed it head-on, so it was not really a problem for us.” Jeff agreed. “That’s what we really try to preach, especially on the operation side,” he said. “We’re not here to remove people. We’re here to remove waste so we can find better spots for people.”

“We’re doing this because we see it as a growth opportunity. The automation may eliminate some manual tasks, but that doesn’t translate to cutting employees. Growth can also mean greater opportunity for the existing workforce.”

Stacy Hiquet, Vice President of Talent Acquisition and Training